When chronic wasting disease creeps into your deer woods someday, don’t let its tortoise-like start make you think it will remain forever at such low levels that you dismiss it as a “political disease.”

Instead, think of it as a plane rolling slowly onto the runway, lumbering along as it gains speed, and then — just as you think it will never take off — blasting airborne into a fast, steep climb. Like it or not, CWD is not going away, and no one knows where it’s going next.

And make no mistake: The situation in whitetail country is getting worse. Here are 10 things you might not know about CWD.

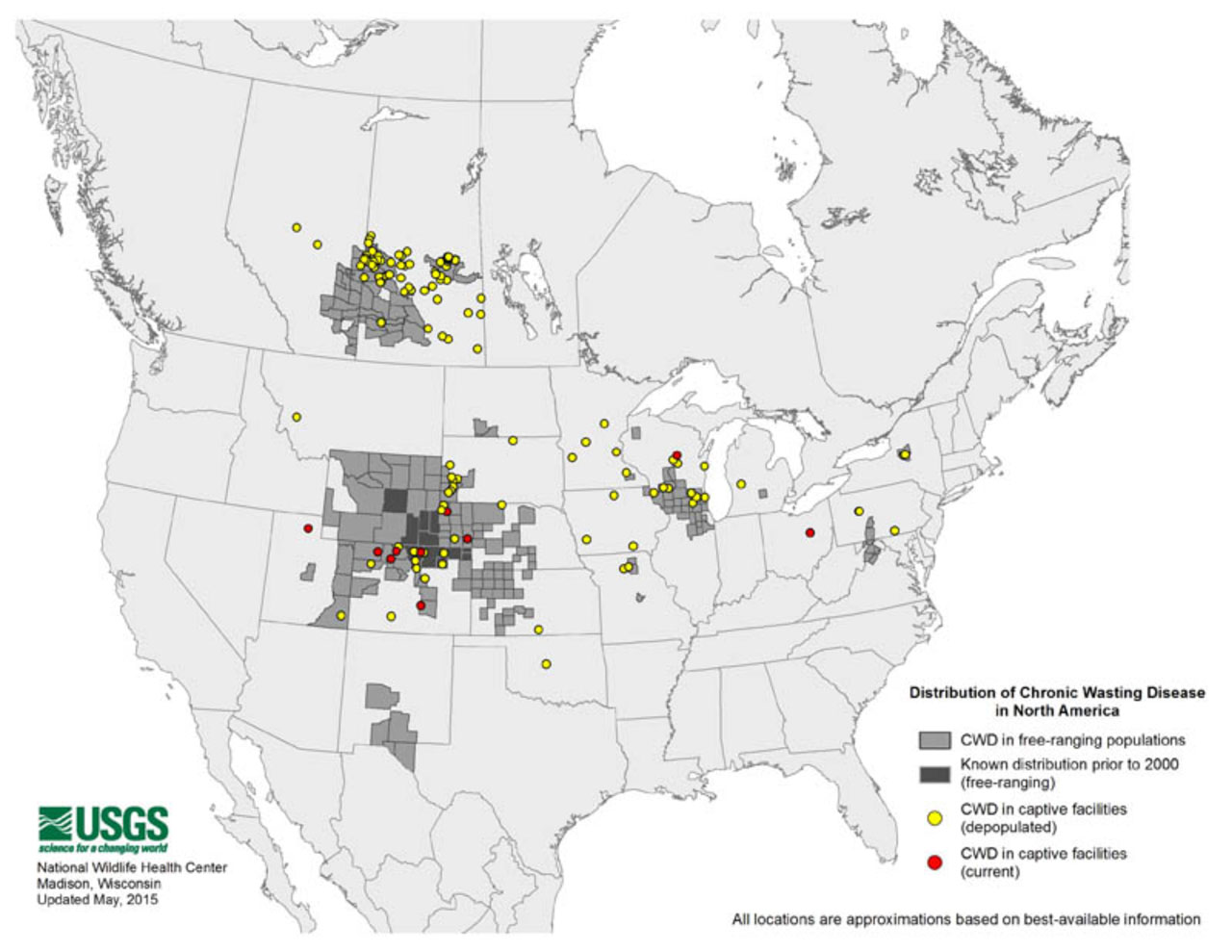

1) CWD has been found in wild deer in 20 states and two provinces.

When Michigan officials killed and confirmed CWD in a sickly doe near Lansing this spring, it became the 20th state to document the disease in the wild. CWD has also been found in Wisconsin, West Virginia, Texas, Utah, Colorado, Illinois, Iowa, Kansas, Maryland, Minnesota, Missouri, Nebraska, New Mexico, New York, North Dakota, South Dakota, Virginia, Pennsylvania and Wyoming. It is also well-established in Alberta and Saskatchewan.

Most of those states and provinces have also found CWD in privately owned deer farms. Other states that have detected CWD only in fenced facilities are Ohio, Oklahoma and Montana.

2) CWD is Expanding its Range.

One sick deer does not make an epidemic, but it shouldn’t be dismissed as a fluke, either. When Wisconsin first detected CWD in February 2002, it was found in just a handful of counties west of Madison, the state capital. Since then it’s established itself across the southern third of the state, and is spreading northward along the Wisconsin River corridor.

Further, even though Wisconsin has reduced its sampling efforts to track the disease’s spread and infection rates, the Department of Natural Resources is documenting record numbers of sick deer. During the 2014 deer seasons, Wisconsin tested 5,414 deer, the second-lowest number of samples in its 14-year CWD-testing program. Even so, the DNR documented a record 6.1 percent disease rate. That’s three straight years the infection rate exceeded 5 percent of tested deer. It’s also the third straight year the number of sick deer exceeded 325.

Make no mistake, CWD is slowly spreading it’s way across North America’s deer population. It’s only a matter of time before it reaches your neck of the woods, if it hasn’t already.

CWD is also worsening in Alberta, Canada. Tests in 2014 found CWD in 74 of 2,048 mule deer tested in Alberta, a 3.6 percent infection rate. And even though bucks are usually twice as likely as does to carry CWD, Alberta’s male-female infection rate was 5-1 in 2014. CWD’s geographic distribution in eastern Alberta also expanded farther up the Battle, Red Deer and South Saskatchewan rivers.

3) CWD Densities are Increasing.

Once CWD appears, it not only keeps spreading outward, it also infects increasingly more deer where it’s established. For instance, after CWD was found in southwestern Wisconsin 13 years ago, infection rates stayed in the single-digits for several years before jumping after 2009.

In 2014, in fact, the infection rate in north-central Iowa County passed a record 40 percent for adult bucks (age 2½ and older) and 22 percent for adult does. Further, CWD rates for that area’s yearling bucks and does was 18 percent and 15 percent, respectively.

Further, an area just east of there, where CWD was found in low numbers 13 years ago, is climbing even faster. Northwestern Dane and northeastern Iowa counties already have disease rates of 27 percent for adult bucks and 12 percent for adult females.

4) CWD is always fatal.

Although some deer are less susceptible than others to CWD, none appear immune to it, and none that contract it survive. Once a deer is infected, it has about 18 to 20 months to live. Deer typically look healthy for about the first 16 months they carry the disease, but then their appearance and behaviors start declining visibly. Those outward signs include staggering, heavy drooling, increasingly visible ribs and spine, and patchy looking hides.

No deer recovers from CWD. It’s a death sentence. Deer stricken with CWD eventually lose their fear of humans as their health declines.

5) Wisconsin has the most reported infections.

Although CWD is more widespread geographically in Wyoming among mule deer and whitetails, Wisconsin has documented more CWD cases — 2,840 — than any other state or province. Illinois is next with nearly 410, and West Virginia has found nearly 175 positive cases. Further, every state bordering Wisconsin — Michigan, Illinois, Iowa and Minnesota — has now found at least one CWD-infected wild deer. And remember: Wisconsin has scaled back its testing in recent years after lawmakers cut funding for the state’s CWD efforts.

Missouri, meanwhile, reported 16 new cases of CWD in wild deer after conducting its 2014 tests. The “Show Me” state has confirmed 29 cases since discovering CWD in 2010 at a private enclosure. One of 2014’s diseased deer was a buck from outside the state’s initial six-county CWD containment zone. Missouri has also found CWD in at least 11 captive deer.

6) CWD Prions Can Move Through Plants

Most scientists believe CWD is caused by a rogue protein called a “prion.” A few scientists, however, believe prions are a symptom, not a cause. Either way, prions are not living organisms like viruses or bacteria. Therefore, prions cannot be “killed” by freezing, burning or cooking at high temperatures. They can remain active indefinitely in soils. Recent research has also found that prions can pass through root systems and up into the leaves of plants, which might then be eaten by deer.

Although no one has proven deer can become infected by eating contaminated plants, recent research suggests it’s possible. Sandra Pritzkow, a researcher at the University of Texas Medical School in Houston, found “wild-type hamsters were efficiently infected” by eating prion-contaminated plants, including CWD.

7) Prions Can Move Through Dust

Because prions can remain active indefinitely in soils, they can get taken in by deer eating from acorns or other foods lying on the ground. Recent research also indicates that prions could become airborne in dust particles, and possibly breathed in.

Kevin Gough, a researcher at the United Kingdom’s School of Veterinary Medicine and Science, detected prions circulating in dust on a farm contaminated with sheep scrapie. Scrapie is in the same family of diseases as CWD and mad cow disease (in cattle). Gough and his fellow researchers wrote: “The presence of infectious scrapie within airborne dusts may represent a possible infection route, and illustrates the difficulties that may be associated with the effective decontamination of scrapie-affected premises.”

8) CWD Vaccines in their Infancy

Is there any way to stop CWD? Ongoing research for a CWD vaccine is showing promise, but the consensus seems to be that vaccines are more likely to work in game-farm situations than in the wild. Not only might vaccines prove too expensive to administer to millions of free-ranging deer over much of the continent.

Even so, a Colorado State University study in 2014 reported an experimental vaccine partially prevented CWD. Eleven deer were exposed to CWD in this study, and then five were treated with varying doses of the vaccine, while six received placebos. Within two years, the six deer receiving placebos were infected with the disease and lived about another 20 months. However, of the five receiving a vaccine, the one receiving the highest dose was still alive late last year. The treated deer survived an average of 30 months, roughly a year longer than unvaccinated deer.

9) Research Money Is Drying Up

Meanwhile, even as CWD expands its range and worsens its infection rates, money to study it is disappearing. When CWD was found east of the Mississippi River in 2002, the U.S. Department of Agriculture declared it a crisis. Soon after it imposed strict guidelines for importing hunter-killed deer, elk and moose from Canada; and sent millions in aid to states to help monitor the disease.

A decade later, however, the USDA’s Animal and Plant Health Inspection Service decided CWD didn’t require nationwide attention. When cutting $14 million in 2012 for CWD monitoring, APHIS wrote: “Since these are local or regional disease-spread issues, state and local governments should assume a more active role, and better anticipate and plan for future needs.”

Deer carrying CWD usually look healthy for the first 16 months they’re infected, but usually die two to four months after symptoms begin to show.

Most states, however, didn’t increase their efforts to monitor the disease or study its many unknowns. In 2013, for example, researchers like Professor Michael Samuel at the University of Wisconsin-Madison was pessimistic he would ever again find money to study why CWD is increasing at faster rates roughly 30 miles west of the state’s flagship university and internationally acclaimed research institute.

“It’s disturbing, but CWD research is on the way out,” Samuel said.

10) No Proof CWD Can Infect Humans – Yet.

Even though scientists have yet to find any evidence that CWD can jump the species barrier and infect humans, no one is declaring it can’t be done. After all, for much of the 1980s people were confident that infected beef couldn’t transmit mad-cow disease to humans, but eventually scores of people in the United Kingdom died of a variant of Creutzfeldt-Jakob disease, the human form of these diseases.

Dr. David Clausen, a Wisconsin veterinarian, cautions that prions might be capable of mutations that eventually allow it to infect humans. After all, as prions continually cycle through deer, scavengers, plants, predators and other living things, it’s impossible to predict how the prions will change.

Conclusion

As CWD slowly advances its way across the North American deer herd it is still unclear what impact it will have on the future of deer hunting. However one thing remains certain; if funding continues to decrease for research and hunters continue their crusade against the thinning of deer populations to curb the spread of the deadly disease the future of the sport is facing one of its biggest challenges.

By

By