Those who chase whitetails during Wisconsin’s late-season bowhunting season often dub it bowhunting’s toughest challenge.

It’s not only cold, but the deer have been hunted since early September, making them increasingly wary of hunters toting everything from bows to rifles to muzzleloaders. The 2018-19 bowhunting season, for instance, opened Sept. 15, which means every deer still standing at sunset Jan. 6 – the season’s final day – survived 114 days of hunting pressure.

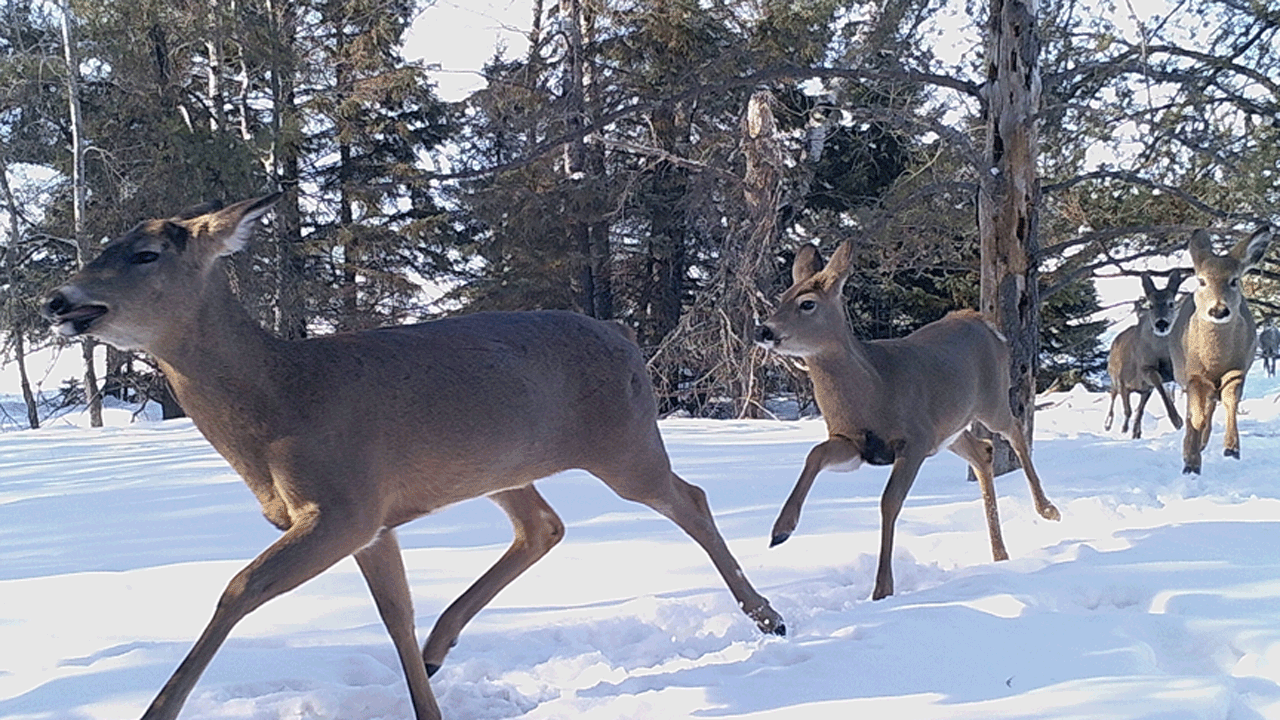

Cold, snow and wary deer make bowhunting especially challenging in Wisconsin’s late archery season, which closed Jan. 6.

Granted, some deer have it easier than others, judging by how many feed leisurely in fields on December afternoons as we drive through farm country. Some lucky deer rarely see or sniff a hunter after opening weekend of Wisconsin’s gun season.

But no matter where deer hang out in December, they seldom pause to verify danger. They snap their white tails to attention and flee the way they came.

Further, bowhunting usually means 15- to 25-yard shots, which requires silent, unseen stealth as you pull a bow to full draw. That’s no easy task in foliage-free winter woods, where hunters feel exposed among bare-branched trees. Likewise, hunters can’t count on foliage to disguise their sounds. All those leaves now lying beneath snow once rustled in the wind or crunched beneath hooves.

Maybe that’s why I’ve had no luck with whitetails during Wisconsin’s late bow season, but I’ve taken several in December with muzzleloaders or centerfire rifles the past two decades. I don’t minimize those accomplishments, but it’s easier to bring home venison when your lethal confidence range is 10 times greater than with a bow.

And it’s not like I never tried late-season bowhunting. I’ve often shivered in treestands and huddled in ground blinds since first bowhunting in 1971. As I scrolled down the years in my hunting log recently, I verified nearly five decades of late-season bowhunting futility.

Sharp broadheads, accurate arrows and good shot placement ensure short tracking jobs in the winter woods.

But I can explain!

Well, maybe. Sometimes.

For my first 20 years or so, archers received only one deer tag. If you filled it before gun season, you were done for the year. And sometimes other things took priority. Between work, holidays, work commitments, late-season gun-hunts, occasional ice-fishing jaunts, and out-of-state hunts for deer, elk or pheasants, I spent many days on bowhunting’s inactive list.

This past month, though, I sneaked out often for short, late-afternoon bowhunts in a treestand near home. Things looked promising the first evening when a doe led two fawns into range near dusk. At least I assume it was an adult doe and its two young-of-the-year offspring. By late December I sometimes struggle to see a size difference unless they stand at attention near each other.

That threesome walked slowly and warily toward my setup. They approached head-on, never turning or veering to offer a good target for my arrow. At 10 yards one deer drifted uphill and two slid downhill from my stand, making it impossible to monitor all three with a glance. With shooting light slipping away, I took a chance and drew on the uphill deer at 15 yards.

Almost instantly I heard a commotion downhill as hooves punched through crusted snow. Just as I centered my bow’s sight-pin on the uphill deer, it fled in three graceful bounds, white tail waving. I let down from full draw, conceding defeat.

The next evening, five deer entered my edge of the woods about 4:15 p.m., but fled before reaching bow range. They seemed bothered by a neighbor’s barking dog, even though it seemed too far to pose a threat. But what do I know? The deer probably know the dog’s range better than I do.

I saw nothing three straight dusks when returning to the woods. Still, I went out for a final sit an hour before dark, still feeling optimistic.

Sure enough, five deer sneaked in unseen from behind my treestand as the sun set, and reached bow range before I heard them. When I turned to look, the closest three whirled around and danced back the way they’d come. The two farther back stopped to watch the first three departing.

That was my chance. But as I pulled my bow to full draw and anchored to shoot, my arrow fell from the bowstring and swung loosely from the arrow-rest. What the heck? That never before happened in 48 years of bowhunting.

Self-serve kiosks, like this one at Hartman Creek State Park in Waupaca County, give hunters more convenient sites to get their deer tested for chronic wasting disease. This is particularly handy when hunting in the cold, dreary days of the late season.

Somehow the deer didn’t hear the arrow clicking and clacking as it swayed. As they watched their departing companions, I let down from full draw, re-nocked the arrow, drew again and put the sight-pin behind the closest deer’s foreleg.

A second later my three-blade expandable broadhead struck where I aimed, and the deer was mine. After skinning and deboning the adult doe Monday, I drove to Hartman Creek State Park, and dropped off its head and upper neck for chronic wasting disease tests.

I doubt the deer will test positive for CWD, but stranger things have happened. For instance, I had just arrowed my first late-season deer in a lifetime of bowhunting.

By

By