Many folks don’t know that until 50 years ago, Wisconsin’s cars and trucks killed more deer by accident than bowhunters did on purpose.

In fact, some of us can remember when Wisconsin whitetails truly were few in number, bows were one-string novelties, and cedar arrows far outnumbered aluminum. We even thought fiberglass hunting shafts were revolutionary luxuries in 1973, and had no idea that carbon/graphite arrows would start their ride to dominance in another 15 to 20 years.

Meanwhile, bow-killed deer were considered feats of luck or incredible skill, and bowhunters were forever trying to earn respect for their craft and its equipment. Many gun-hunters disdained archery gear and bowhunters, and barely changed their tone when compound bows took over by the late 1970s.

Even so, bowhunting was usually well-represented by its pioneers, many of whom became legends. The man most recognized for proving and publicizing the effectiveness of modern bows and arrows was Michigan’s Fred Bear. He was not only a skilled archer, but also a masterful manufacturer and communicator. During the 1950s and 1960s, Bear hired cameramen to film his worldwide big-game bowhunts, which featured recurve bows he designed for the Bear Archery Co. He then broadcast his feats on national TV, and published his stories in books and magazines.

Bear didn’t establish bowhunting’s legitimacy alone, of course. In Wisconsin, Roy Case of Racine, Larry Whiffen of Milwaukee, Art Laha of Weyauwega and the fabled professor Aldo Leopold of Madison all did their part. And nationally and internationally, men like Howard Hill, Ben Pearson, Glenn St. Charles and Bill Wadsworth patiently built its credibility.

Still, no one rivaled Bear’s ability to not only bowhunt and make its tools, but also spread its story. At least that’s what another bowhunting pioneer, Jim Dougherty, said in January 2008 after receiving the Fred Bear Archery and Bowhunting Communicator Award, a joint presentation from the Archery Trade Association and Professional Outdoor Media Association.

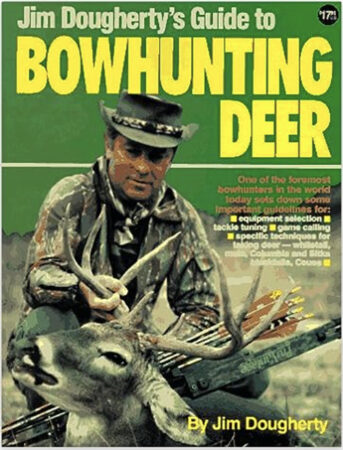

Dougherty was a native Californian who began bowhunting before Eisenhower’s first election in 1952. He was also a prolific writer, who seemingly never stopped cranking out articles until drawing his last breath eight years ago on Sept. 21.

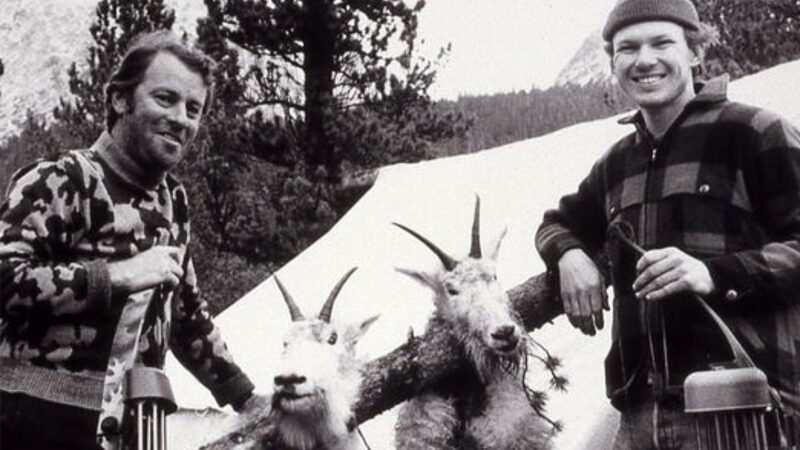

Those lucky enough to read Dougherty’s articles in hunting magazines appreciated how he married wit and humility with solid information. He traveled extensively, bowhunting a variety of North American big game across 33 states and four Canadian provinces. He also journeyed south to bowhunt Mexico, and across the Atlantic Ocean to bowhunt Africa. He remained consistently funny, humble and objective through the years and miles until cancer finally killed him days shy of his 79th birthday.

In an interview after receiving the Fred Bear award in 2008, Dougherty said Bear believed good hunting stories remain vivid long after hunters enter antler scores in a record book.

“There’s a lot of icons in this sport, old and new, but Fred Bear was the one everyone looked up to,” Dougherty said. “He was a great man. He walked a good line. I don’t mean this in a derogatory way, but many guys try to make their name by shooting a lot of big stuff. Fred Bear shot a lot of big stuff too, but he didn’t make a point of it.

“He was more about storytelling, and he was the greatest storyteller I’ve ever heard. He was funny and self-deprecating. He never tried to pump himself up into something larger than life. Someone else always did that just because they wanted to. He didn’t ask them to. That’s why I admired him. He knew how to promote our sport.”

Dougherty grew up bowhunting rabbits and deer with recurve bows and cedar arrows, but like most hunters switched to compound bows and aluminum shafts as technology improved. He never had much patience for those who scorn modern equipment.

In M.R. James’ book, “Unforgettable Bowhunters,” Dougherty said: “Bowhunters collectively are bowhunting’s worst problem. We squabble and fight among ourselves like turkey poults over a grasshopper. We were fighting over equipment when I was 15 and we still are. Why?”

“The cop-outs, when it comes to equipment, want to blame it on some manufacturer. (But) manufacturers build what the public tells them they want.”

Those who read Dougherty always praised his humor, too. In his brief speech after receiving the Fred Bear award — a bronze replica of Bear’s legendary Borsalino hat — Dougherty recalled a favorite memory of Bear.

“You know, I tried to steal Fred’s hat years ago, but before I got out of the room he said, ‘Jim? You forgot my hat.’”

Dougherty then laughed and held up the bronze award bearing Bear’s name. “I don’t know what else to say, but now I’ve got his hat!” Dougherty told the crowd.

One thing was certain that day: Bear would have said Dougherty earned it.

By

By