Researchers who studied a cave complex in Spain recently concluded that Neanderthal hunters likely turned one of the chambers into the world’s oldest known trophy room.

The title of their scientific paper sounds more scholarly, of course. It reads, “A symbolic Neanderthal accumulation of large herbivore crania.”

“MeatEater” TV/podcast host Steven Rinella translated the title this way on Instagram: “A Neanderthal Cave Stacked with a Big-Assed Collection of Euro Mounts.”

Likewise, Arizona wildlife researcher Jim Heffelfinger put it simpler yet, calling the Neanderthal trophy room “the original man cave.”

Neanderthals died out roughly 30,000 years ago, a few thousand years after modern humans first appeared.

Though the word “accumulation” isn’t quite right – skulls and antlers don’t gather like dust or dirty laundry, after all – the study’s stuffy title would probably look good if engraved in wood for display in anyone’s trophy room or man cave.

Including my own. Our downstairs rec room features most of my “large herbivore crania,” including the skulls and shed antlers of deer and moose; skull caps and Euro mounts of elk, pronghorn antelope and white-tailed deer; and full-shoulder mounts of elk, mule deer, pronghorns and whitetails. Most of these critters fell to my bullets or arrows, but I found the moose skulls and antlers while hunting deer in Ontario and northeastern Minnesota.

My current “accumulation” of bones and horns in one specific room wasn’t a formal, long-term process. After moving 130 miles and downsizing into our new home two years ago, we realized our small upstairs lacked the space of our previous kitchen, dining room, living room and hallways.

After my wife shoehorned our TV, couch, recliner, loveseat, coffee table and bookshelves into our new confines, and hung family photos on our modest walls, the living room had room for only five deer mounts. That forced me to cram most of my taxidermied treasures into the downstairs’ one finished room until my remodeling projects expand our display options.

The Neanderthals apparently processed their animals and stored their impressive skulls more deliberately over time, according to a research team led by Enrique Baquedano at the Archaeological Museum of the Community of Madrid. After studying stone tools and other artifacts from the cave complex, Baquedano and his team concluded the chamber with all the herbivore heads had a specific “symbolic use” that excluded “subsistence” practices like butchering or food preparation.

These Neanderthal hunters kept the animals’ carcasses outside while breaking them down for food, tools and other uses. After removing the meat, eyes, tongue and lower jaw from the heads, they brought the skulls to a specific cave chamber.

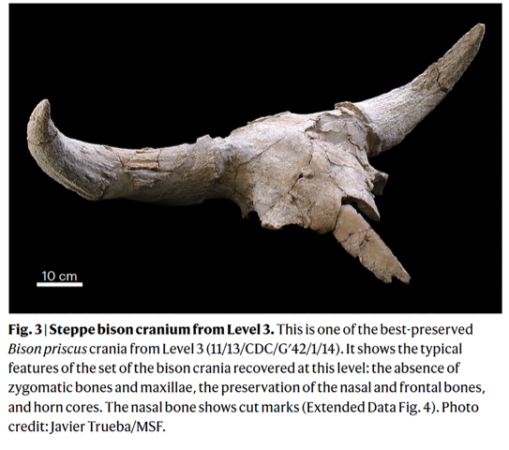

Significantly, each of the 35 skulls in this chamber had “appendages” of some sort, either antlers, keratinous horns or bony horn cores. The skulls came from 14 Steppe bison (now extinct), three auruchs cattle (extinct), 11 bison, five red deer, and two narrow-nosed rhinoceroses (extinct).

To read the 23-page paper in the scientific journal Nature Human Behaviour, hit this link: https://rdcu.be/c5oKH. Its findings clearly show modern-day hunters weren’t the first to admire horns and antlers, and burn energy hauling them home for display.

Likewise, Dan Born of Northfield, Minnesota, wasn’t shocked to read of the Neanderthals’ trophy room. Born did his master’s degree work on Nebraska’s Hudson-Meng Bison Bonebed, a nearly 10,000-year-old Paleo-Indian kill site where bones from about 600 butchered bison collected over hundreds of years.

“No one has found even one skull cap among all those bones,” Born said in a phone interview. “Part of the kill site was destroyed accidentally when the rancher who discovered it excavated a stock pond, but that doesn’t explain all the missing skull caps. The most likely explanation is the Paleo-Indians who hunted there for centuries found the skull caps fascinating enough to carry off, despite their size and heavy weight.”

Born said archaeologists still haven’t accounted for those missing skull caps.

The researchers in Spain, meanwhile, can’t compare their findings with similar Neanderthal “trophy rooms.” As Baquedano writes: “To date, no site exclusively related to symbolic activity has been identified in the Neanderthal archaeological record. … Parallels with ethnographic examples might be useful in addressing this question.”

Baquedano, however, finds those parallels in modern hunting: “Today, the accumulation and display of large mammal skulls in the form of hunting trophies is linked to sport hunting. Similar practices for varying purposes have … also been documented for the most recent hunter-gatherer societies. Indeed, cultures worldwide have invested animal skulls with a strong symbolic content and have protected or displayed them with due attention.”

You might mention Baquedano’s research from now on when houseguests ask about your mounts, antlers and skulls. Some folks just won’t get it, of course. Critics will likely assume it’s about insecurities and bragging rights, but we know it’s more about memories and storytelling.

Even so, nonhunters aren’t the only ones to assume the worst or ascribe motive. Biologists hosting the Southeast Deer Study Group meeting in 2004, for example, asked me to give an after-dinner speech to explain why “the hunting media” focus so intently on antlers, which some of them called “horn porn.”

Earlier that day, one speaker said “deer hunting culture today seems preoccupied with money, products and large-antlered bucks.” One clever speaker even collated the pages of several recent hunting magazines and calculated the buck-to-doe ratio of their deer photos. I laughed along with everyone. Fair point.

Given eight hours to craft a witty comeback, I asked a simple question from the lectern that night: “What’s the buck-to-doe ratio on cave-wall paintings?” I said horns and antlers fascinated hunters long before we had paper, let alone photos or TV signals.

Each antler is as unique as human fingerprints, but prettier and more memorable. Therefore, I found it more challenging to choose eye-catching cover photos for deer hunting magazines than turkey hunting magazines. “If you’ve seen one strutting turkey fan, you’ve seen them all.”

Yes, my home has two full-body mounts of gobblers and several fans, but I have far more skulls, antlers and horns. As the Spanish researchers suggest, hunters throughout time have invested such artifacts with similar reverence.

And some Neanderthals continue sharing their investments from beyond the grave.

By

By