When attending the annual Southeast Deer Study Group meeting in Chattanooga, Tennessee, in February 2003, hundreds of biologists and researchers from Eastern states took turns thanking the fates that they weren’t from Wisconsin. Roughly a year had passed since Wisconsin announced Feb. 28, 2002, that it identified chronic wasting disease in three deer near Madison.

Fifteen more years have since passed, so when about 300 deer experts gathered here in March for the 40th SEDSG meeting, many felt frustrated that they still lack a science-guided way to avoid being the next Wisconsin.

In a not-so-subtle jab at Wisconsin “deer czar” James Kroll of Texas, one wildlife veterinarian said: “No one likes listening to us because we give them bad news and tough choices. They’d rather hear everything will be fine; that CWD is just a political disease and big bucks still abound.”

Others challenged attendees to remain realistic and cooperative. Kelly Straka, Michigan’s wildlife health section supervisor, said biologists won’t sway public opinion by wearing a lab coat and scribbling scientific solutions on blackboards with white chalk.

And quoting Aldo Leopold’s “A Sand County Almanac,” Straka encouraged them not to quit, because the problem is real:

“One of the penalties of an ecological education is that one lives alone in a world of wounds. Much of the damage inflicted on the land is quite invisible to laymen. An ecologist must either harden his shell and make believe that the consequences of science are none of his business, or he must be the doctor who sees the marks of death in a community that believes itself well and does not want to be told otherwise.”

Many states in whitetail country are now dealing with chronic wasting disease.

How deep are those “marks of death”? Well, everyone in this audience seemed well aware that mature bucks in parts of southwestern Wisconsin have 50 percent CWD-infection rates. They also knew Wisconsin’s disease rates started spiking in 2005 when public pressure forced the Department of Natural Resources to cease hostilities against the always-fatal disease.

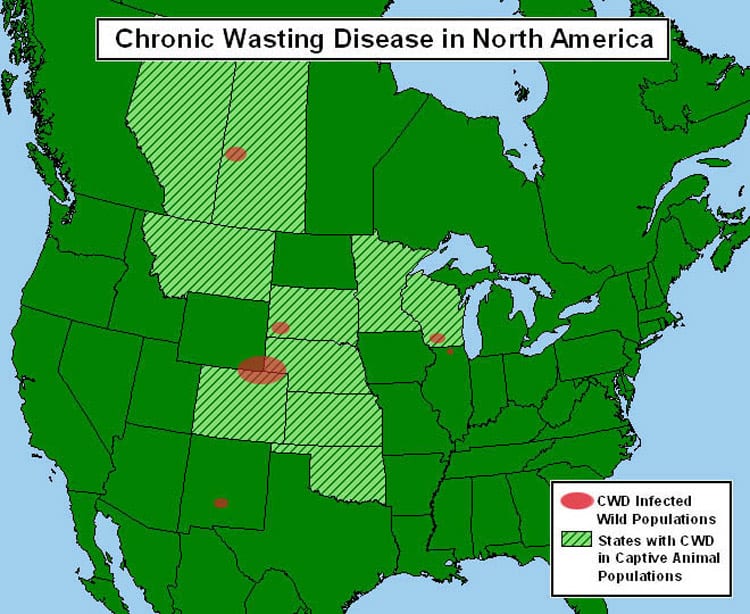

But how times change. On Feb. 27, 2002, CWD had been found in free-ranging deer in only three states: Colorado, Nebraska and Wyoming; and in captive elk in six states and one province: Colorado, Kansas, Montana, Nebraska, Oklahoma, Saskatchewan and South Dakota.

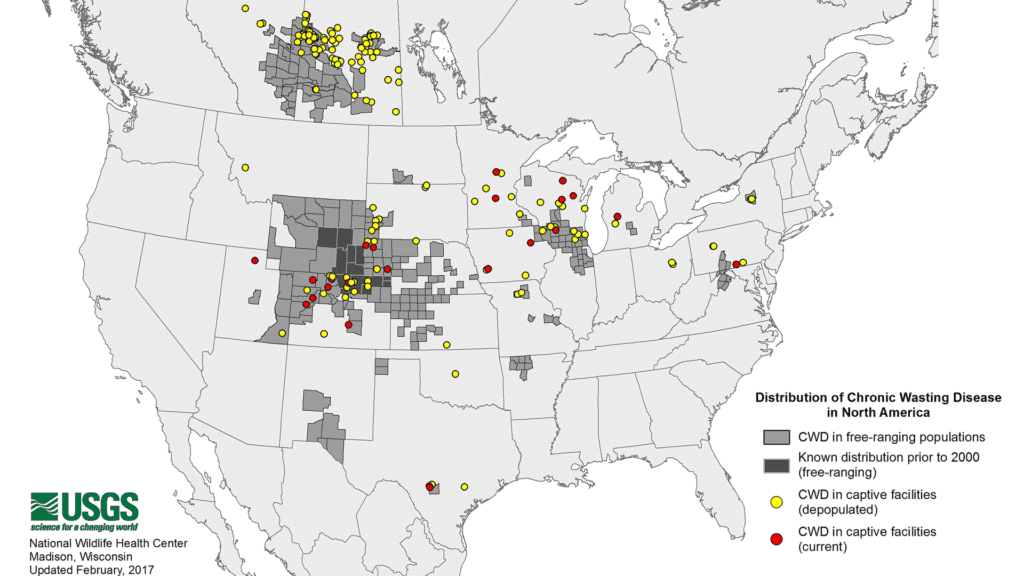

Today, CWD is confirmed in captive and/or free-ranging deer or elk in 24 states and three provinces. Those totals include 75 captive herds in 16 states, and free-ranging deer or elk in 22 states.

Eradicating CWD looks impossible, given its traits and distribution. Still, John Fischer, director of the Southeastern Cooperative Wildlife Disease Study in Georgia, cites some important motivations for trying to contain and control it.

For one, research suggests heavily infected deer herds cannot thrive in the long-term. Two, data on CWD prions (the agent thought to trigger the disease) and experience with other animal prion diseases suggest it’s prudent to minimize human exposure to them. Three, hunters will likely quit hunting deer where infection rates hit 50 percent.

After all, hunters might not worry about contracting the disease themselves, but most won’t assume that risk for children and grandchildren.

Fischer also cautioned that an area’s first confirmed CWD case is probably not its first actual case. In a report he co-wrote with Colorado state veterinarian Michael Miller, Fischer said: “Given imperfect surveillance approaches, incomplete or inaccurate knowledge about local exposure risks, and the insidious progression of an outbreak in its early stages, the first case detected in a locale is rarely the first case that has occurred.”

This map shows the known distribution of chronic wasting disease in 2003.

In fact, follow-up investigations often find CWD in larger areas and at higher rates than expected, which make it seem the disease is spreading faster. In Arkansas, for example, after the state identified its “first” CWD case in February 2016, expanded sampling found 79 additional cases within two months.

In addition, after a flurry of surveillance testing in the early 2000s across Eastern states, funding for research shrunk and apathy – even hostility — set in. Testing the past decade has been intermittent. As Fischer and Miller wrote: “Although (testing) efforts were well-intentioned, many were too flawed or short-lived to provide reliable information on disease absence. … Statements exhorting that examination of a few hundred (or even a few thousand) harvested animals (proves an area free of) CWD rarely are supported by data.”

Wisconsin, for example, hasn’t conducted statewide sampling since 2003, and current efforts under-test many infected areas and surrounding counties because submitting samples is voluntary. In addition, testing areas with new CWD cases has not been systematic or comprehensive in Wisconsin.

How extensive should surveillance tests be? Research in Missouri’s Franklin County underscores sampling’s complexity, noting that deer, CWD and hunters are not spread evenly across the landscape. Scientific sampling requires planning and precisely placed shooters. To find a disease rate of 0.4 percent with hunting alone, Missouri’s research suggests of Franklin County – which covers 931 square miles — could need 1,500 samples in a given year.

For perspective, if the Wisconsin DNR wanted to verify that disease rate in Washburn County, which had one verified CWD case in 2011, it would likely need about 1,365 samples in a given year. Granted, Washburn County’s 853 square miles differ from Franklin County, Missouri, but the most samples the DNR collected from Washburn County hunters the five past seasons was 688 in 2012. Since then it collected 345 in 2013, 264 in 2014, 132 in 2015 and 191 in 2016.

This map shows the known distribution of chronic wasting disease in 2016.

None of that matters to some folks, of course. Visit any hunting forum on the internet, and you’ll find echo chambers where like-minded folks claim CWD is a hoax or government conspiracy. As Nick Pinizzotto, president/CEO of the National Deer Alliance told the SEDSG crowd, hunters want to hunt deer, not deal with CWD.

Pinizzotto said that might be their hope, but “hope is not a strategy.” And, like Straka, he invoked another American conservation hero, Theodore Roosevelt, to encourage more CWD work and cooperation between hunters and biologists.

“In any moment of decision, the best thing you can do is the right thing, the next best thing is the wrong thing, and the worst thing you can do is nothing.”

By

By