Our do-it-yourself elk camp straddles a creek just yards downstream from a 3-foot waterfall that plays the prettiest background music to ever lull a weary bowhunter to sleep.

We settled on this spot in September 2013 after getting crowded out of our original campsite 2 miles north, which we used from 2006 to 2012. We concede that our first campsite in the Caribou-Targhee National Forest had more amenities, including an adjoining hiking trail and aging outhouse whose roof and door long ago rotted away.

But with trails and amenities come people and competition. You show me a hiking trail on public lands, and I’ll show you hikers, hunters and harried families stumbling from it into your campsite, no matter how many miles and obstacles lie between you and the trailhead.

In contrast, we’ve never had a two-legged visitor wander into our current campsite. No trails start, stop or pass by here, and we think we’re the only ones who know the best bushwhacking routes into the surrounding valleys, coulees and mountains.

We do get visitors, however, perhaps even more regularly than at our original site. But they aren’t hikers or fellow bowhunters asking how to find a distant truck or SUV. These visitors include moose, beavers, otters, a badger, mule deer and an occasional mouse. We haven’t entertained a red squirrel since 2012, probably because we’re too far into the meadow to coax them from their trees and fallen logs.

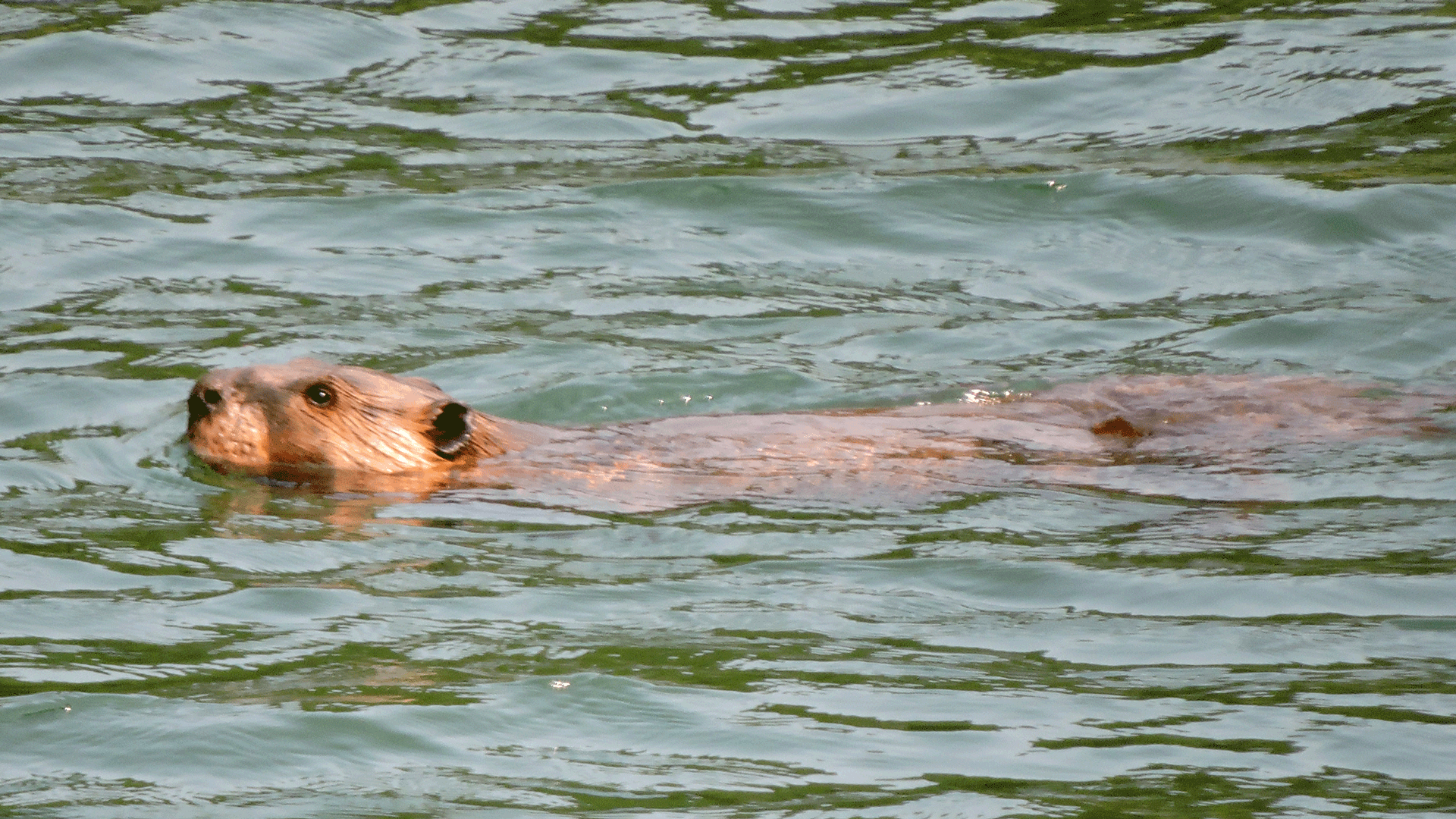

Our first four-legged visitor this year was a beaver that descended from the grass- and brush-choked valley above camp. We’ve spotted dams and lodges along the creek upstream, and been startled when beavers slap their broad tails upon their ponds to signal alarm.

A beaver swims in a flooded creek downstream from its lodge and dams.

Later that day, my friend Mark Endris heard what sounded like a flock of birds chirping back and forth from the water’s edge. But when he poked his head around the tent’s corner to look, he spotted an otter family swimming and hunting along the creek’s mouth. He counted six sleek heads shimmering in the shallows, occasionally periscoping their necks for a better look at him.

Three mornings later, Endris and I were making breakfast when we heard loud splashing in the flooded creek a few yards away. Given how the waterfall obscures all other sounds around camp, we first thought the beaver or otters had returned. Just as quickly we knew something much larger was out there in the water-covered weeds.

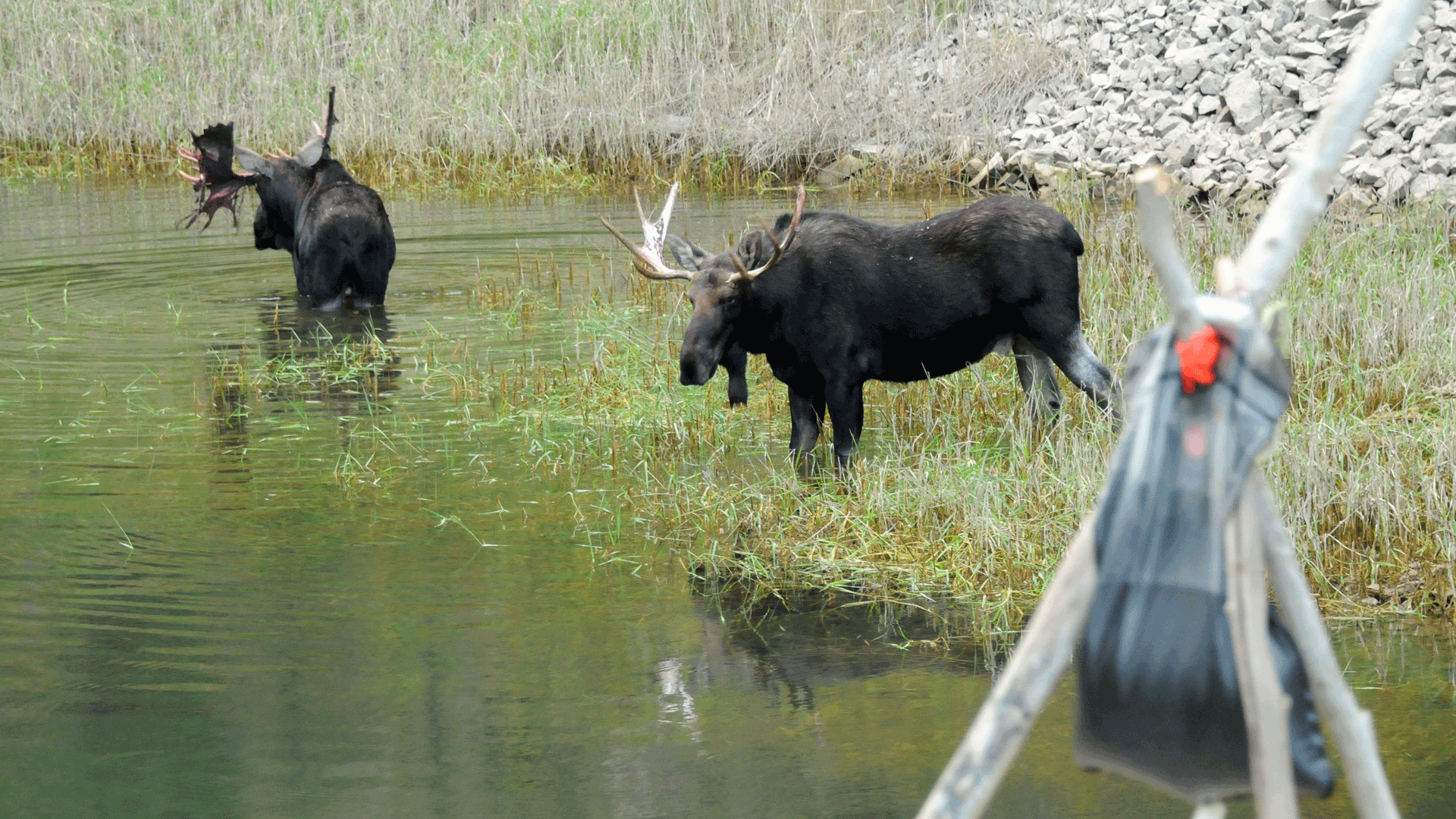

Being 60-somethings, neither of us write “OMG!” or exclaim “Oh my god!” But when we looked out, I wouldn’t have thought less of Endris if he had let one slip. Not 20 yards away two bull moose strode through the shallows within yards of my cedar boat, their bells swaying and dripping water beneath their necks.

Two bull moose feed and drink in a flooded creek at the edge of Patrick Durkin’s elk camp in Idaho.

We had watched the same two bulls feeding the previous afternoon in the meadow above camp, stripping the leaves off willow limbs and raking their antlers through brush to help shed their dying antler velvet. When Endris first spotted the bulls on Labor Day, he noticed their antlers were still covered in black velvet, a soft skin that supplies blood and nutrients to the antler while it grows from spring through summer.

As the bulls walked past the edge of camp, shreds of bloody velvet hung from their antlers and dragged the water as they drank and fed on weeds. They looked up occasionally to stare at Endris and me as we snapped photos and recorded video, but they were far more intent on eating and drinking.

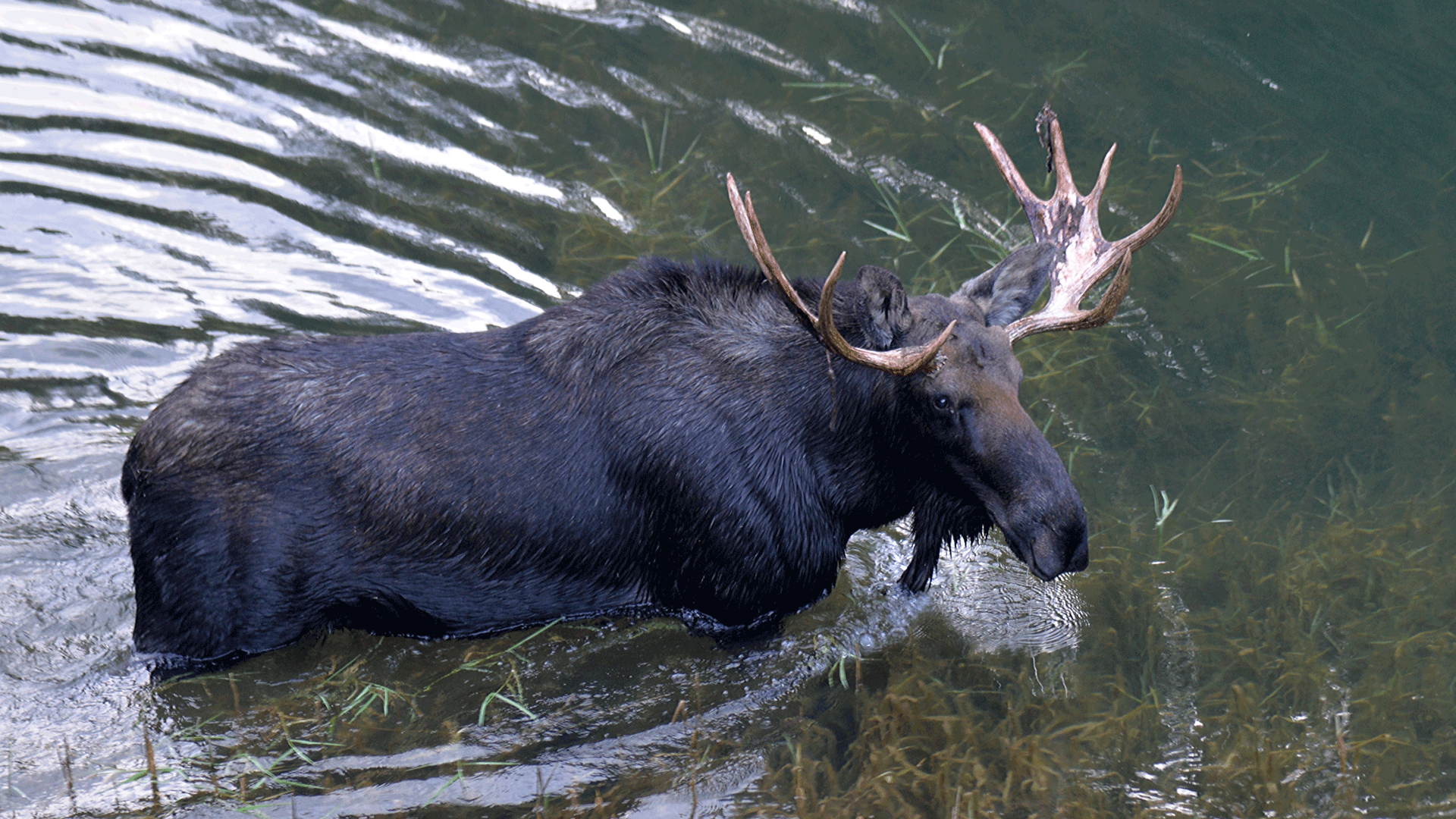

The smaller of the bulls seemed friskier and more restless, and soon swam across a deep section of the flooded creek to our side, disappearing behind a rock formation. I walked from beneath our tent flap, ascended the rocky knoll and saw the bull in shoulder-deep water below. It moved toward me a few steps, but didn’t rock its antlers or lay back its ears to signal aggression, so I kept photographing.

A bull moose walks along a creek’s flooded shoreline.

A minute later, it swam back toward the other bull, and then bucked and splashed water with its front hoofs when within range of its buddy. That seemed to irritate the bigger moose, which turned and walked back up the valley toward the willow thickets. The smaller moose followed, but paused to rake, twist and abuse a young pine and a nearby aspen with its antlers.

With all that rubbing, velvet shredding and antagonistic antics of the smaller moose, Endris and I figured the rut was nearing, and these two would soon go their own way to search for cows to breed. Sure enough. We never saw them again during our final week in camp.

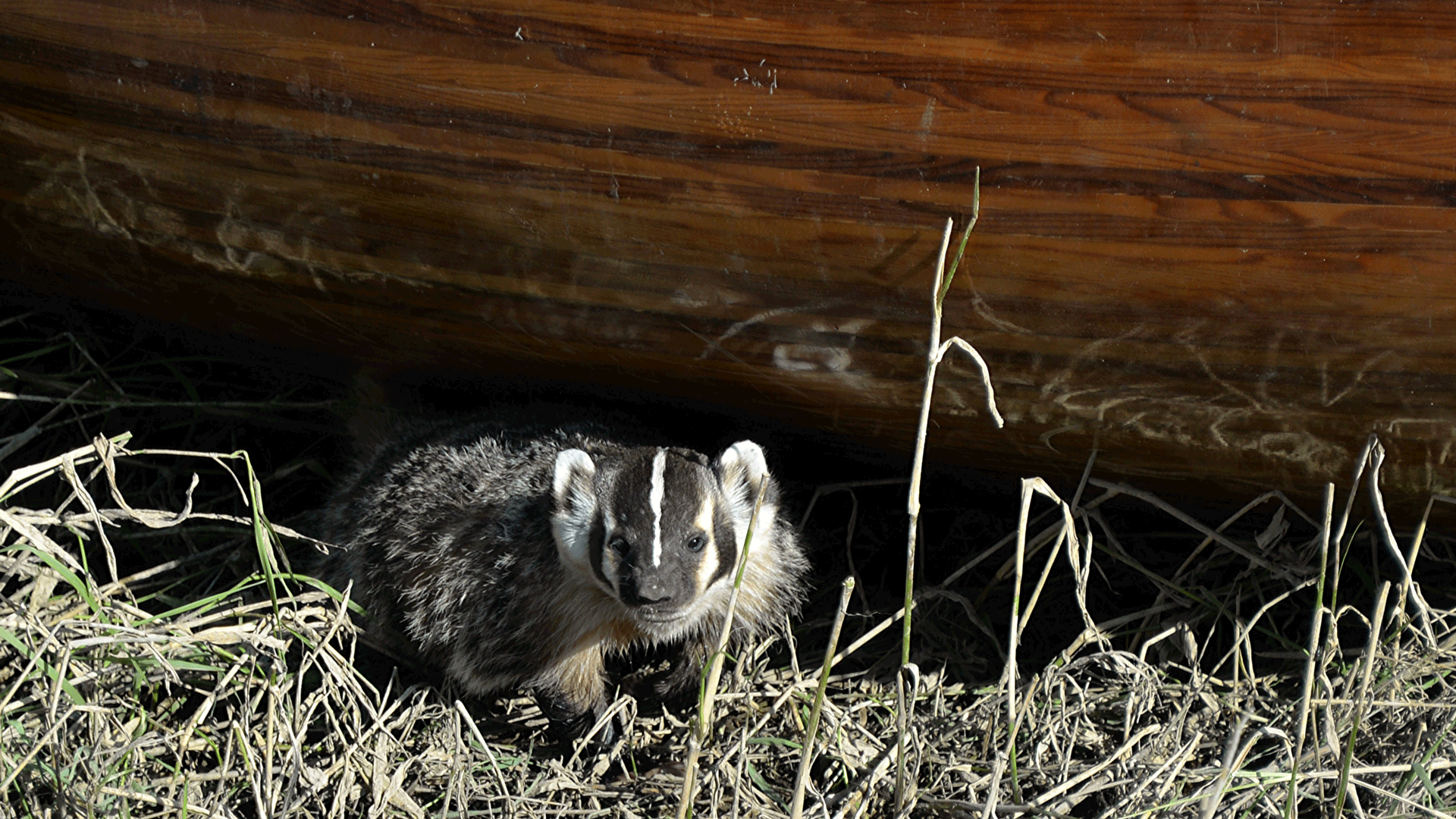

Still, we weren’t alone. A few days later Endris and I were lounging around in late afternoon when I caught movement 5 yards away. A bushy, rust-colored tail passed behind a log securing a tent line. I hissed at Endris and pointed, not knowing what would pop out from behind the log.

Seconds later a low-slung badger waddled into view. I’ve only seen a handful of wild badgers in my life, but never one with a burnt-orange tail. The badger disappeared by the time we grabbed our cameras. When we sneaked out to search for it, Endris climbed the nearby rocky knoll and I looked by the boats.

A badger steps from the shade provided by Patrick Durkin’s cedar boat.

Almost immediately I heard a low rumbling sound, but couldn’t pinpoint it because of the waterfall’s background noise. The sound grew louder and intensified when I stepped closer to the cedar boat. There, 5 yards away in the boat’s shade, its butt backed to the water’s edge, the badger sat glowering and growling.

I backed away. I did not want to antagonize a cornered badger. Endris and I kept our distance, and the badger eventually sneaked away, its movements barely telegraphed by the tall grass.

Whew. We were relieved it fled.

Unlike waterfall music, there’s nothing peaceful or charming about a growling badger.

By

By