Given our hunger for over-the-counter solutions to everything from bunions to baldness, perhaps it’s no surprise that people continue to buy “deer whistles” for their cars nearly 30 years after science discredited these cheap bumper ornaments.

After all, if people would rather buy miracle-pills than forsake foods that make them fat, gassy or prone to heartburn, they’ll also seek painless solutions to deer-vehicle collisions.

Tell the truth – have you ever bought a pair of deer whistles?

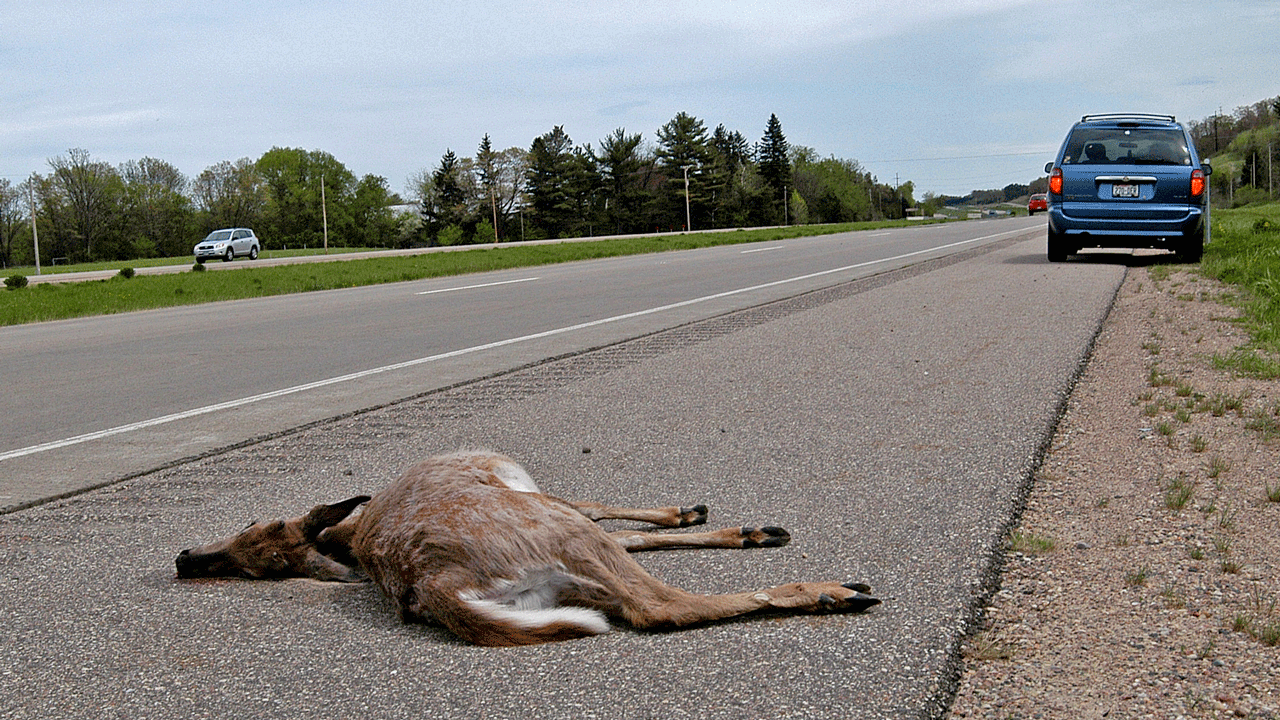

Plus, given that these crashes kill about 200 Americans each year, boost car-insurance rates ever higher in deer-rich counties, and require about $2,000 in repairs after an “average” collision, who wouldn’t be tempted by placebos?

But if you really believe deer whistles protect you from jaywalking whitetails, you probably also think they’re technological forerunners to Captain Kirk’s force field on the star ship Enterprise.

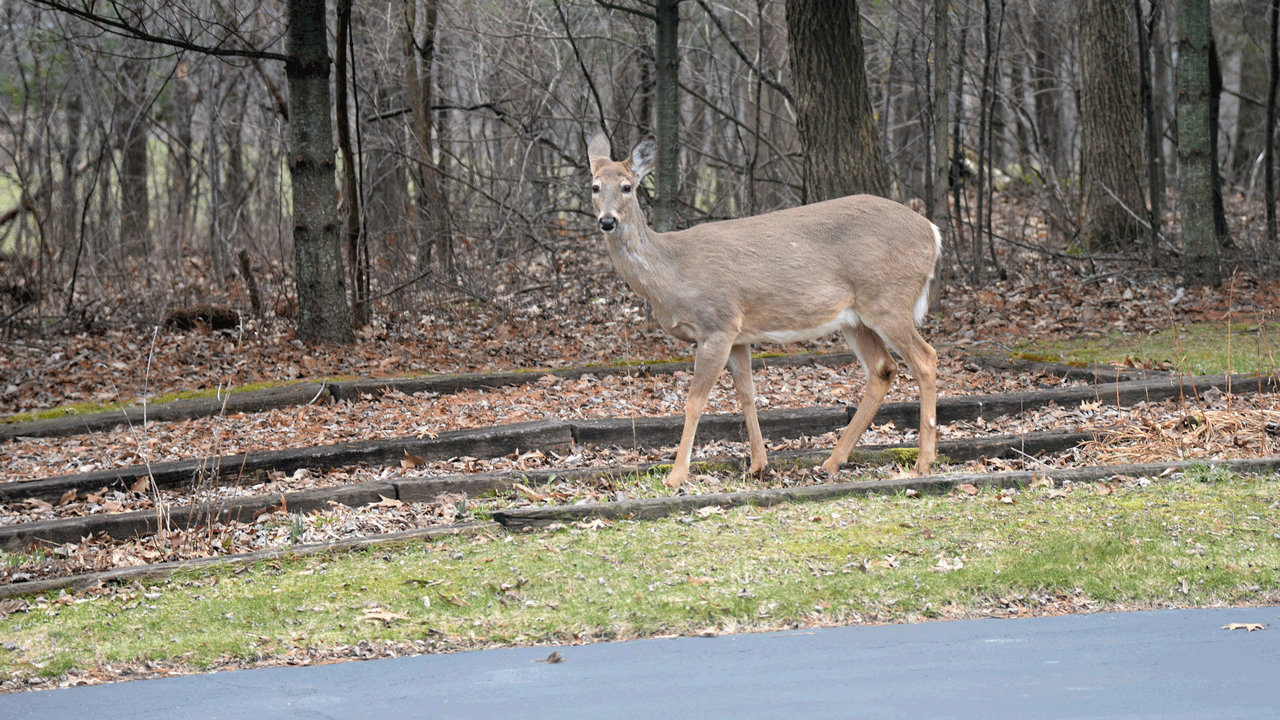

Why don’t deer whistles work as advertised? Hmm. Where to start? How about deer behavior. Have you heard the expression, “as frustrating as herding cats”? The only reason to mention cats is that deer make lousy house pets. When startled or frightened, whitetails leap in unpredictable directions, change their minds in a nanosecond and bound the opposite way.

About 200 Americans die each year in deer-vehicle collisions.

Next, consider the deer’s sense of hearing. Deer-whistle manufacturers claim their products emit ultrasonic sounds that deer, but not humans, can hear. That’s curious, because widespread research indicates that although deer detect normal sounds better than humans, they’re little better than us at detecting ultrasonic frequencies.

In fact, research into deer whistles and deer hearing by Sharon Valitzski, a graduate student at the University of Georgia, verified that suspicion about 10 years ago. Using semi-tame deer at the university’s research facility, Valitzski and fellow researchers broadcast five sound frequencies at levels greater than 70 decibels, and made 406 observations of how the deer responded.

When addressing the 30th annual Southeast Deer Study Group meeting in Ocean City, Md., in February 2007, Valitzski reported: “Deer could hear sound in this (ultrasonic) range, but they couldn’t hear it very well. It had to be heard at 70 decibels in order to be registered by deer.”

Next, the researchers mounted sound-generating equipment to a 1993 Buick station wagon and drove past observation points on Georgia’s deer-congested Berry College Wildlife Refuge to see how deer responded. They also tested the deer by driving past with their sound equipment turned off.

After recording 319 test observations on the various sounds, two of which were ultrasonic, Valitzski reported only one sound produced a statistical difference in deer behaviors: a low-frequency bass sound. Yes, much like the thumping you hear when youngsters drive by with music vibrating their windows.

Before you download the nastiest rap or hard rock music from iTunes for your car stereo, read what else Valitzski said about bass sounds: “Deer exposed to this sound were more likely to cause a motor-vehicle collision than they were to prevent one.”

Georgia researchers found that when deer respond to noises, they tend to cause collisions, not avoid them.

Remember the “herding cats” analogy? Most deer hunters can tell similar stories. Who hasn’t fired a gun at a deer and had it run straight at them? Flight responses can’t be predicted.

Even so, the responses Valitzski recorded were yawns compared to one generated at the University of Wisconsin-Madison in the late 1980s by Tim Lawhern, then a graduate student. Lawhern, who went on to a career in wildlife law enforcement, tested deer whistles on seven species of deer, including elk and whitetails.

When Lawhern created a shrill sound from one of the whistles – a sound humans can also hear — a bull elk charged him. Fortunately, Lawhern was on the other side of the facility’s fence. The bull slammed into the fence, snapping off a 2-by-4 fence post. The enraged animal then bugled and urinated.

Is that road rage or what?

Most of us can probably relate to that angry bull. Who hasn’t been tempted to respond impolitely when someone pulls alongside in heavy traffic, their car pulsating with sounds that could sterilize frogs?

By

By