Just as I was sliding toward sleep inside my camper trailer a few seasons ago, it subtly squeaked and trembled as my nephew squirmed and rolled over in the bunk overhead.

This restless turning and rolling had been going on more than an hour. My inclination was to mutter loudly, “Could you give a couple of more groans and kicks to make sure nobody else in here can sleep, too?”

Before irritation won out, however, I remembered what he was going through. The opening of deer season was just a dawn away, and he was too excited to sleep.

I could relate. Although I now usually sleep peacefully on deer season’s eve, I realize it only came from experience. My nephew’s restless turning and sighing made me recall a sleepless night many years before as I anticipated my first deer hunt at age 15.

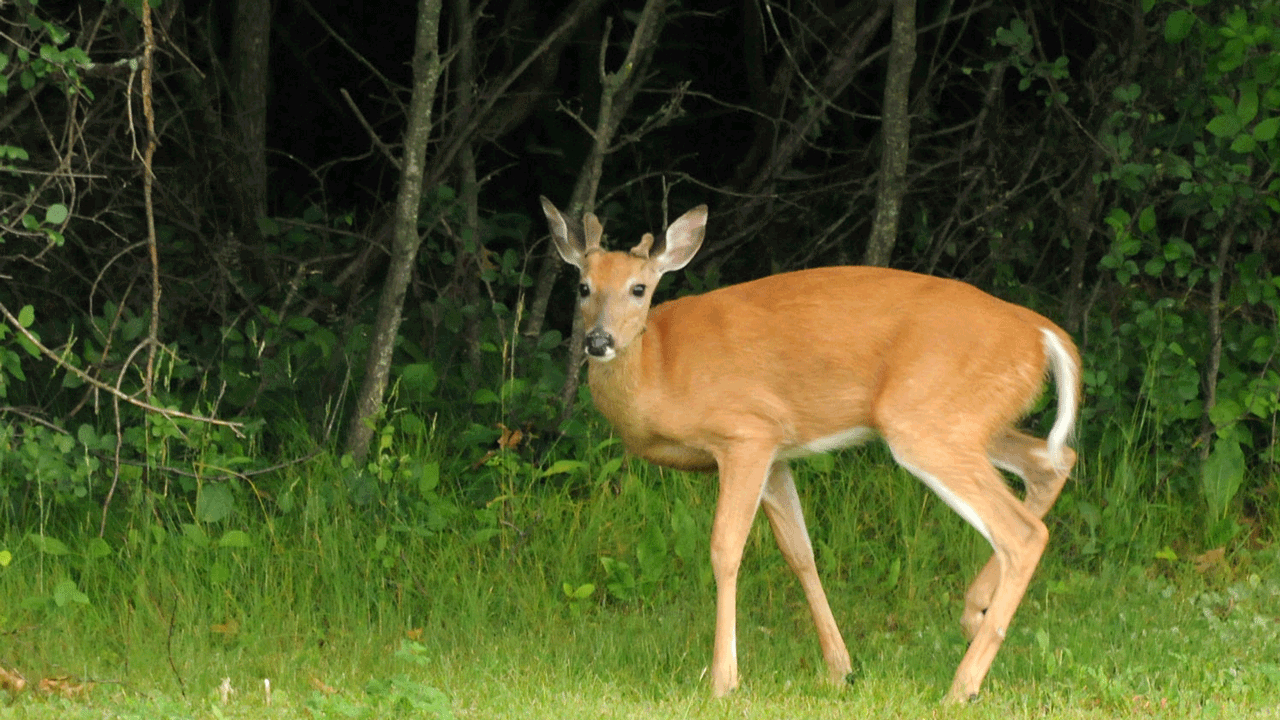

Beginning hunters can’t help but lose sleep the night before deer season when thinking of bucks they might see the next morning.

How big is opening day to new deer hunters? Maybe the fact I can recall the date of mine — Nov. 20, 1971 — gives some indication. I also remember the statewide deer kill for that year’s gun season was less than 71,000; 70,835, to be exact. The bow kill that year was a shade higher than 6,500. I take perverse pleasure in knowing my first deer hunts occurred during the worst deer season we’ve had in the many decades since.

Hunters never know what they’ll see on opening day of deer season. They might see a trophy buck or possibly just a little buck growing its first sent of small spikes.

I spent the eve of that hunt in a deer camp in northern Wisconsin. My father had arranged the hunt. Dad hadn’t hunted deer since Eisenhower or Kennedy was in office, but he knew I was aching to go, so he imposed on a good friend to take me.

Every deer seen during hunting season causes a rush of adrenaline.That friend was Charlie Merkle. Now that I’ve introduced a couple of youngsters to hunting, I appreciate Merkle’s patience and hospitality even more. I felt like a big shot the night before the hunt as Merkle and his friend, Kermit Hermanson, included me in their conversation. After supper, they leaned back, clasped their hands behind their heads, and talked about previous deer seasons in the North Woods. I leaned back and clasped my hands likewise, but I have no idea what I contributed to their talk.

Later, we stopped at a local tavern, where my newfound hunting partners were asked to explain the presence of “the kid.” Then the barkeep offered some commentary on deer management:

“They say we need to shoot more deer because if we don’t, a lot more of them will starve this winter. Well, why don’t we go to the hospital and pull the plugs on people who won’t make it through the next few months?”

Every deer seen during hunting season causes a rush of adrenaline.

It was my first taste of bio-emotional deer management. Little did I know that such sentiment wouldn’t change much over the next 50 years, nor had it changed much in the 50 years before 1971.

Shortly after returning to the cabin, we checked our gear and turned in. Before long, I could hear Merkle and Hermanson were sound asleep. I was at full alert. I wanted to sleep, but all I could think about was the overlook where I would sit the next day. Merkle had walked me to the spot that afternoon after our five-hour drive from Madison.

I imagined a doe cresting a nearby humpback, with a buck not far behind. I plotted how I would react, where I would aim, and how the deer would drop quickly from the fatal wound I inflicted.

I retraced our route to the stand from the cabin, trying to remember landmarks and Merkle’s other navigation tips. I must have made that walk 50 times in my mind, and still I couldn’t sleep. And even though it had never worked before, I tried counting sheep. This time it failed even worse. The sheep became deer, and I lined up my sights as each one jumped over the fence in my mind.

Finally, opening day arrived, and then it was quickly gone. I passed most of the day on that stand, and saw four deer, including a sub-legal spike buck. I never did more than watch. Nor did I ever feel tired, even though I couldn’t have slept more than an hour the previous night.

Funny. After my nephew’s first day of deer hunting the next day, I never heard him complaining either of being tired.

By

By