After tossing pruned cherry limbs and winter’s snow-felled pine boughs onto our burn pile, I paused to inspect the bowhunting targets on my backyard practice range.

Other than looking a bit faded and tattered around their chest inserts, my 3D deer targets looked sturdy despite another year of ice, snow, rain, sun, broadheads, field points and chickadee nest-tunnels down their throats.

Yes, I’ve replaced the inserts at times, and fashioned rope-and-stick tourniquets to reunite their legs and bodies, but compared to my bundled-newspaper targets of the 1970s and ’80s, my modern targets are indestructible.

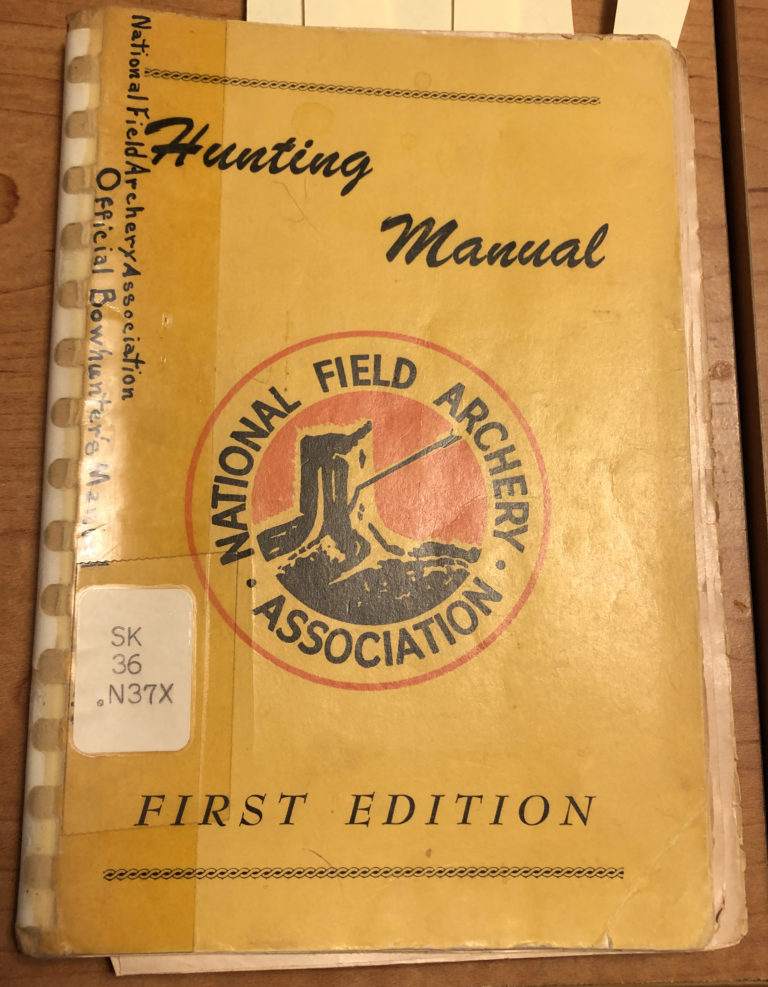

That comparison made me think about a bowhunting book my friend Mike Foy recently donated to my home library. Much has changed since the National Field Archery Association published its 1958 “Hunting Manual,” also called the “Official Bowhunter’s Manual.”

It has a plastic-comb binding, and many pages flop loosely, their edges long since unbound. But each page is present and accounted for, which isn’t surprising, given Foy’s nature.

The “Hunting Manual” features roughly 100 pages of advice from that era’s famous bowhunters, including Michigan’s Fred Bear and Wisconsin’s Roy Case. Bear, of course, founded the Bear Archery Co., and traveled the world with a camera crew to build bowhunting’s credibility by arrowing everything from bull elk to a bull elephant.

Case, meanwhile, is the father of Wisconsin bowhunting. He recorded the state’s first bow-kill of the modern era by arrowing a spike buck in Vilas County during the December 1930 gun season.

Case’s two-page article in the “Hunting Manual” is titled “Advice to Bow Hunters,” and originally appeared in the August 1947 issue of Archery magazine. The chapter mostly details how to manually sharpen broadheads and keep them lethally sharp

Case recommended a finely serrated cutting edge “like that which the butcher whets on his knives.” He continued: “It is not an edge one would like on his pocket knife or razor. This type of edge has tiny forward pointing needle sharp—I almost said barbs—of course they aren’t barbs but I hope you get the idea.”

Case’s nuanced sharpening instructions required hours of labor with files and whetstones to arm a four- or five-arrow quiver. That made me wonder why today we don’t scorn replaceable-blade broadheads and all who use them.

After all, I recall plenty of fussing and whining in the mid-1970s when compound bows replaced recurves and longbows. But that caterwaul can’t compare to the ongoing bigotry toward crossbows. We constantly hear that “real” bowhunters log hours of practice and purposely hunt the “hard way.”

If degree of difficulty is the standard separating “real” from “pretend” bowhunting, why don’t the citizen boards that oversee hunting regulations ban replaceable-blade broadheads and require we all use traditional Ben Pearson Switchblades and Bear Razorheads with bleeder blades?

The “Hunting Manual” highlights many other changes in modern bowhunting. Even with the great advances in speed and accuracy for today’s compounds and crossbows compared to yesterday’s traditional bows, we still arrow most deer at less than 20 yards. Further, most bowhunters today recommend shooting deer no farther than 30 or 40 yards.

That was conservative counsel in the 1950s. In a chapter titled “Hunting the Wisconsin White-Tail,” Otto Wilke recommends practicing mostly “between 15 and 30 yards, where we expect to shoot our deer,” but to also practice out to 60 yards. He noted, “For (me), good sportsmanship and the bow have parted company at 60 yards.”

Wilke, however, discouraged running shots: “No doubt it is thrilling to accidently hit and kill a deer on a flight shot, but it is an act of God, and nothing for man to brag about.”

Earlier in the book, however, Fred Bear offered advice on arrowing moving targets. In the first chapter, “Hunting with a Bow,” Bear wrote:

“There will be opportunities to shoot at running game. The problem of ‘how much to lead’ will be perplexing. No fixed rule can be stated except to say that most of us do not lead enough, and that most misses are made by the arrow going behind the animal. Try consciously to over-lead.

“On a walking deer, for instance, at 40 yards the arrow will strike from (18 inches) to 2 feet behind where aimed, providing the deer does not hear the bowstring and stop. On a deer that is running slowly or merely loping, the lead at the same distance will be between 8 and 10 feet, depending on how fast a bow and how light an arrow is used. If he is running fast the lead must be 20 or 30 feet at 40 yards.”

Bear then discussed whether to swing with the fleeing animal and then pull ahead, release and follow through as if using a shotgun; or holding ahead and shooting “when the time seems right.”

For bowhunting thick woods, Bear recommended picking an opening ahead of the deer: “The best he can do is to hold on an opening and loose when the animal gets in a position he thinks will give the proper lead.

Good practice for this type of shooting is to have someone roll cardboard discs along the ground or down a hill and shoot at them from various distances.”

Meanwhile, if you hold fast to beliefs that hardship and deprivation purify a bowhunter’s soul, don’t forsake Wilke’s footwear advice: “For dry weather, moccasins are tops, though some people’s feet are not strong enough to wear them.

Tennis shoes, or sneakers, and heavier moccasins are next. For morning dew and wet weather, try house-slippers (inside) galoshes.”

Wilke also offers downhome advice for camouflaging your face: “If you cannot get a good tan before the season, swipe some of your wife’s rouge and, between it and the stove poker you should be able to obliterate your beaming countenance.

Never mind your manly beauty; it is not an asset in this conquest.”

Likewise, thinly disguised attacks on other bowhunters’ equipment preferences are no asset in protecting bowhunting’s heritage.

We can thank the “Hunting Manual” for these 62-year-old reminders.

By

By